She shouldn't be facing deportation or the barrel of a gun.

She should be home celebrating her birthday, but the activist knew what was at stake.

Less than an hour earlier — just after 2 a.m. when the temperature drops enough that an Arizona breeze mingled with perspiration makes the summer heat almost bearable – she’d imagined falling into bed, sleeping late and waking up to read birthday messages.

Máxima Guerrero had just turned 30. Even during a pandemic, her friends had remembered. But there wasn’t time for celebration.

On this last Sunday in May, Máxima sat in the dark, staring at a swarm of police officers barricading streets and blocking protesters from leaving a downtown Phoenix demonstration demanding justice for George Floyd and an end to violent policing.

After years of organizing civil disobedience actions — rallies against former Sheriff Joe Arpaio, protests to remove immigration officers from Phoenix jails, and fighting injustice — Máxima knew momentum for real change is rare. With this many people in the streets across the nation, this was their chance to be heard.

She also knew the faces behind Arizona's fatal police shooting numbers.

If Máxima didn’t monitor police during the demonstration and something happened, even to one person, she wouldn’t forgive herself.

For most of the night, the protest in central Phoenix remained peaceful. Police in riot gear. Protesters carrying signs: Black Lives Matter. Defund Police. It was a fragile accord.

She was heading home with other legal observers when a friend suggested a final check of the remaining protesters. They drove down Adams Street and parked. There were maybe 50 protesters left. Most were heading home.

"It seems to be people are walking away, so maybe we should just go,” she says. "All of the sudden there are officers who are blocking all the streets."

Phoenix police officers moved in unison to corral protesters. People all around her were arrested.

Law enforcement experts call it kettling, a tactic used to control large crowds.

Civil rights advocates call it a trap.

“In all the times of being at a rally, I’ve never seen (police) vehicles being used on a road to block people from leaving,” Máxima says. “Police pointing guns at us, yelling at us to get out of the car.”

“I’m thinking, 'I have DACA. I know I have to let folks know what’s happening to me,'” she says.

Máxima knew being a so-called Dreamer with temporary legal status through the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program wouldn’t protect her from deportation if she were arrested – not in Arizona, not in Trump’s America.

She’d spent years figuring out how to survive without papers. One arrest could change everything.

“I’m thinking, 'Cooperate with whatever is happening because you never know what could be the possibilities with police,'” she says.

Four to six police vehicles surrounded them. Officers ordered her friend out of the car first. Hands up, they shouted.

Counting on seconds to contact her fellow legal observers before officers reached her, she quickly messaged: "We’re about to be arrested."

She got out of the car, hands above her head, officers ordering her to turn around. She felt a jolt of steel handcuffs against her wrists. No one told her why they were being arrested. No one read them their rights, she says.

In the days that followed, she'd pass through the jail of Maricopa County Sheriff Paul Penzone. Four years earlier, she had worked with her community to unseat former Sheriff Joe Arpaio for illegally targeting people like her. She had hoped Penzone would do better.

But inside Penzone's Fourth Avenue Jail, a judge told Máxima Phoenix police had arrested her for felony rioting and she was transferred to ICE officers — one step toward deportation, one step away from the same detention centers where she'd helped organize protests to free migrants.

Máxima would quickly realize Penzone wasn't the solution. He campaigned for Latinos' and immigrants' votes, but kept ICE officers in his jails just as Arpaio had done. He maintained an ICE partnership that sent migrants to detention centers for deportation proceedings before they had been prosecuted with a crime.

Now, about to lose everything — her freedom, her family, her home — she knew if she wasn't deported, she would take on Penzone as she had Arpaio.

‘You’re not a citizen'

Máxima was 5 when she crossed the U.S-Mexico border with her little brother. Not so young that she can't remember the sound of rock and gravel under her feet that night in an isolated stretch of the Sonoran Desert between the border sister cities of Nogales.

Her mother had fled an abusive relationship to work in the U.S. Máxima is often asked when she realized she wasn’t an American citizen.

You go to school and learn the same things as other students, you memorize the Pledge of Allegiance. You go home and watch the same shows. Then, one day, she says, you realize you don’t have the same rights as your friends born in the U.S.

“I don’t think it was ever explicitly told to me,” she says. “But it was also never hidden. Other family (members) were being deported.”

Máxima was 17 the first time it felt real for her.

“I was trying to get a job during high school and filling out the application,” she says. “I just wanted to work at Subway.”

The oldest of her siblings, Máxima remembers her mom’s face when she told her she wanted to work, help pay the bills, have a little extra to spend with friends.

“She said, ‘You don’t have a Social Security number,’” Máxima says.

Then came the day she had to tell a friend. Her government class was taking a trip to Washington, D.C.

Máxima loved learning about politics and policies that shape the country. Her friend urged her to go. They could see the nation's capital and room together.

“She said, ‘You should come to the trip, don’t worry about the money, my dad will pay,’” she says. “I just tried to keep stalling. And she kept saying, 'Ask your parents.'"

When Máxima couldn’t make any more excuses, she said, "'I can’t go because something might happen to me. Immigration might be at the airport.'”

Máxima didn’t have to explain more. Her friend was Mexican. The girls went to school at South Mountain High, where students are predominately Latino and many are from families with mixed immigration statuses.

It was 2008 and her friends were making plans for a future — applying to college. An adviser told Máxima that students with a G.P.A. at the top of their class qualify for free tuition at Maricopa Community Colleges.

She had a 3.7 G.P.A. This was a real chance to afford college. The paperwork requested a Social Security number.

“You’re not a citizen,” she remembers thinking.

She was 17 with no driver’s license, no job, no money for college, no citizenship.

“I got into a deep hole of not being hopeful,” she says.

'Show me your papers'

She'd spend hours searching for community on MySpace. She also started taking the free community bus to the public library near her house in west Phoenix.

“I’d be like searching, 'no papers,'” she says. “This was before we had anything about being 'undocumented and unafraid.'”

She stumbled onto something called the DREAM Act, a political movement led by undocumented youth advocating for a path to citizenship.

Máxima knew MySpace grouped people based on shared interests. She found a high-school friend who also was undocumented and had won a private scholarship for college. She messaged him.

He messaged back: "Hey, I saw some students at ASU who are organizing, you should come to a meeting."

Máxima had never taken a bus that far from her home.

After wandering past Arizona State University's brick buildings and under palm trees, she found the small meeting room and looked around at everyone: Latino students without papers. Just like her.

She remembers thinking, “Who are these people? What are they doing? The DREAM Act? John McCain? Who is that and what are they talking about?”

It was 2009, five years since voters approved Proposition 200, a ballot initiative that required proof of citizenship to register to vote and barred noncitizens from receiving certain public benefits. (The U.S. Supreme Court would later strike down parts of the law requiring proof of citizenship for voter registration.)

Anti-immigrant sentiment had reached a tipping point.

By 2010 the Arizona Legislature was debating a bill that would become the nation’s toughest immigration measure, SB 1070 or the “show me your papers" law.

Young Latinos responded to the nativism and racism with their own movement.

The group at ASU that day would become known as the Arizona DREAM Act Coalition. They would put undocumented youth like Máxima and their families at the center of political conversations.

A dream deferred, not dead

Máxima was learning from these young people who were like her, and who were tired of being second-class citizens in the only place they knew as home.

“They were my age, but they were organizing,” she says. “They were getting petition signatures for the DREAM Act at First Fridays and they were talking about getting passports for an ID. I didn’t even know I could get a passport.”

She remembers long talks about how an ID was a way to show they were someone and they mattered. One kid got a Bank of America credit card and showed it off — it had his name and photo on it.

“We were just creating any possibility to have some form of identification,” she says.

Máxima remembers learning how to ask for petition signatures by explaining the DREAM Act and how it could help hundreds of thousands of young people without legal status.

Walking up and asking, "Will you sign this?" terrified Máxima, a shy 20-year-old.

“It was my first time going up to strangers and advocating for something,” she says.

It had been a long time since Máxima let herself think about the future. The DREAM Act offered a way to change things. Soon, she was training other students how to ask for petition signatures, and she didn't just learn who John McCain was, she organized rallies outside the senator's office.

“If we win this DREAM Act, I’m going to be fine,” she says. “I’m going to come out of this hole that I’ve been in. It was that sense of community.”

She spent nights with activists, camping outside McCain’s office in a 24-hour vigil.

Being around undocumented college students made Máxima want to try again to go to college. She found a private scholarship from a California group. It was only $500. But the money would be just enough.

“That was one of the first private scholarships I was able to get,” she says. “I started with one class that summer.”

On the first day of class she boarded the bus with a map, a list of routes, her consular ID.

“I cried on the bus,” she says, “because I can’t believe I can start at Phoenix College.”

Soon the Legislature passed a law requiring noncitizens to pay out-of-state tuition rates.

“Magically, I got this really big scholarship,” she says. "In the back of my head I thought of all the other students who weren’t going to make it that semester.”

No one in Máxima’s family had gone to college.

“My parents couldn’t understand the magnitude of what having this semester in college means and what I had to go through to be able to be there," she says.

Being undocumented, she says, often feels like there's always something or someone else to fight.

“It’s like this struggle that seems to coincide with everything else that’s a struggle,” she says.

Máxima was in class at Phoenix College in December 2010 when the U.S. Senate voted on the DREAM Act.

The measure failed, 55-41. McCain had voted against it.

“I needed to be in community, and being outside of McCain’s office was the only place I knew how to be in community,” she says.

Máxima watched others cry, but she was thinking about why they had lost.

"No matter how much we try to appease … at the end of the day, they are going to hold their party above our humanity, our basic human rights," she says.

She realized it was time to fight back with civil disobedience, time to make politicians uncomfortable.

A LOOK AT SB 1070: A legacy of fear, divisiveness and fulfullment

Power, politics

The fight for the federal DREAM Act was happening against the backdrop of another immigration fight — this one local, over SB 1070.

Máxima understood Arizona was fueling the nation's growing anti-immigrant sentiment and policies to drive out migrants — either out of the state or better, back to where they came from.

High school students in communities of color across the Valley walked out of school in protest. Máxima recognized an awakening in young migrants. They weren’t afraid.

Now 20, she wondered how her life would be different if someone had taught her how to fight back when she was 17, undocumented and still very afraid.

She started to help organize the student walkouts.

Some days were so long, Máxima forgot to eat, got little sleep and spent more time with protesters than her family. They couldn't afford to lose.

Gov. Jan Brewer had the power to stop SB 1070, a measure authored by state Sen. Russell Pearce, a politician with a penchant for stirring xenophobia, that would target families like hers.

Latinos with and without citizenship protested at the Capitol.

Máxima was learning who gets a say in Arizona politics.

"The space that exists at the Capitol – that wasn’t for us,” she says. “It was scary. They told us they could arrest us, but people were still showing up.”

Máxima’s mother pleaded with her to stop protesting.

"I remember one time I was arguing with my mom and I said, ‘If there is something I can do to stop this, I’m going to do it. It’s not just for myself,'" she says.

When Brewer signed SB 1070, Máxima said goodbye to friends whose parents moved to states where they felt safer. Those who stayed grew closer. More determined.

The leaders you see today were just kids then, Máxima says, but they were angry and organizing.

“It was the state saying that I can be a target or anyone that I know or who looks like me can be a target,” she says.

Arpaio’s deputies began immigration sweeps targeting Latino communities.

“We heard stories of people being pulled over and being racially profiled,” she says.

Pearce and Brewer had paved the way for Arpaio to use his department and deputies as a de facto deportation mill. Arpaio broke the law to target, jail and do everything in his power to separate their families, Máxima says.

They wanted Arpaio out. But his anti-immigrant policing had only made the sheriff more popular.

Election after election, no candidate came close to unseating him.

A battle at the ballot box

SB 1070 and the DREAM Act had taught Máxima it wasn't just her voice that mattered, it was who and what she campaigned for. She didn't have papers, but she could sway votes.

For the next two years, Máxima worked with other youths and their families to elect people who cared about migrants.

When Daniel Valenzuela won a seat on the Phoenix City Council, she says, undocumented people felt like they had someone who would take their calls and listen.

“That was one of the first elections where people who couldn’t vote really made the shift, the change,” she says, adding he was also one of the first they would hold accountable.

Máxima campaigned to recall Pearce over his role in passing SB 1070. Even to Máxima — who believed in their power to push for change — a win seemed impossible in a conservative stronghold like Mesa.

Máxima knocked on doors and spoke to people who told her she should be deported. But there were also Latino families who registered to vote Pearce out and Mormon families who listened to the young immigrant tell them she wanted someone who saw her as a human.

Voters recalled Pearce, opting for a Republican who made it clear he cared about immigrants.

“I couldn’t believe it based on the kind of electorate that usually comes out to vote in his community,” she says. “It was a very proud moment I was able to be a part of this movement to stop this man who is making decisions that hurt my people.”

Máxima was learning the change she could make in her own home state, even without a DREAM Act.

“For many of us, it was an understanding that there’s a national political landscape, like for the DREAM Act, but the local political landscape, the local elections affect people day to day, every year and that should be just as important as what we do every four years.”

Toppling America's toughest sheriff

Arpaio was next on Máxima's list.

The Adiós Arpaio campaign sought to register thousands of marginalized voters. It was run by Promise Arizona, a local immigrant rights group, and Unite Here, a hospitality workers union.

People could vote for whomever they wanted, but the groups expected most voters of color in Maricopa County, especially Latinos, would reject Arpaio. They just needed an alternative to Arpaio and someone to convince them their vote mattered.

A political unknown named Paul Penzone was challenging Arpaio. Penzone was another lifetime lawman but campaigned on treating everyone, including immigrants, with respect.

Máxima says Adiós Arpaio wasn’t a campaign for Penzone. It was a campaign for anyone but Arpaio.

Máxima oversaw a team of volunteers who were in eighth grade. After school, they’d meet Máxima, knock on doors and talk to people about voting and how it could help migrant families.

“They knew the impact because they had family members who had been deported under Arpaio’s policies,” she says of her volunteers.

That summer, in 2012, Máxima earned a spot in a week-long UCLA summer program for undocumented students.

Being in LA with other youths gave her a break from the grind of knocking doors.

She was in class when they got word that then-President Barack Obama was about to issue an executive order to shield an estimated 800,000 young undocumented migrants from being deported. If they met certain requirements, including having no criminal record, they’d gain temporary legal status.

“It was sinking in that I don’t have to worry about being deported or I don’t have to worry about figuring out how to get a job,” she says. “Now, I can have all these different opportunities and lift that weight off my shoulders.”

After Obama's announcement, they celebrated at an LA rally. Máxima remembered telling her high school friend that she couldn't go to Washington, D.C., because "immigration might be at the airport." Now, Máxima felt safe in the airport on her way back to Arizona.

“I felt reinvigorated. I felt like, ‘Let’s do this!’”

As Election Day neared, Máxima knew it was unlikely Arpaio would lose.

“I had to look at them and say, ‘Hey, Arpaio won the election,’” she says of her team of eighth graders. “There was this sadness on their faces. We did all we could do but that still wasn’t going to change that we lost the campaign.”

The kids were undocumented or had parents without papers. They knew that when Máxima said it was over that meant Arpaio would continue as sheriff and keep targeting their families.

The kids wanted to keep knocking on doors. She invited them to help pack up the campaign office. She tried again to explain that the election was over, but they'd made a difference. They were part of an effort to register nearly 30,000 new voters, she said.

“It’s a start of the shift and changing the voting culture of our communities,” she says. “We didn’t do it this time, but it’s going to happen in the next one.”

'The best chance that we have'

Máxima joined a wave of young people organizing nationally through United We Dream.

“When I got my DACA, I thought, we have something,” she says. “What about the rest of our families?”

One action took her to the border, in Nogales. Máxima hadn't been there since she crossed from Mexico to the U.S. at age 5.

Now, she was standing on the U.S. side, staring at the wall, a fence that separates cities that are supposed to be sisters.

“I don’t know what words to use but an out-of-body experience,” she says. “If we just removed that, this whole community can be connected, the people and families can be connected.”

One DACA recipient hadn’t seen his brother since he was deported. Máxima saw the siblings weep as they pushed their hands through a fence to hug.

“It’s an abuse of human rights," she says. “It made me more aware of what separation is for families."

"And I was starting to learn and understand about what are detention centers. What are private prisons. Who benefits from people being incarcerated and detained. And getting into that political education and knowledge to change this.”

With DACA she could work, start a business, travel without fear of deportation. But Máxima stayed home. She got a job as a parent liaison at a Phoenix school.

She needed a driver’s license and quick because organizers heard Brewer was moving to ban undocumented immigrants from getting licenses.

Máxima worried about what else politicians might take away.

“I need to take advantage of this DACA program, I don’t know how long we’re going to have it,” she says. “If there’s one thing I can do so that my family doesn’t have to worry about rent and at least we’re investing in our own home, I have to do it.”

At the school where she worked many of the children were undocumented.

“I shared my background, where I was coming from,” she says. “For me, it was just learning about people, people that weren’t politically conscious or cared to be."

She realized advocates and activists were leaving people behind. If you want to change lives, she says, you meet people where they are.

She worked as a parent liaison for two years.

In 2016, she bought her family a home. They were safe and Máxima was ready to fight again.

It was an election year. Penzone was challenging Arpaio again, and community organizers were building on their 2012 momentum.

Arpaio was weakened by lawsuits that had cost taxpayers $70 million, publicity stunts, and a racial-profiling lawsuit for sending deputies to Latino communities, work sites and centers for day laborers to arrest people suspected of being in the country illegally. Evidence showed they targeted people who appeared to be Latino without a reasonable suspicion of a crime.

Máxima knew Arpaio had violated a federal judge's court order to stop his immigration sweeps and that he bragged about his Tent City Jail doubling as a "concentration camp" for undocumented migrants. She listened to Arpaio campaigning for then-presidential candidate Donald Trump, who like the sheriff was campaigning using anti-immigrant rhetoric.

“It’s was like finishing off where we left off four years before,” she says of the campaign to unseat Arpaio.

The grassroots campaign Bazta Arpaio, a play on the Spanish word "enough," needed organizers.

“Immediately, I was like, ‘Yes, where do I sign up?’" Máxima says.

Máxima listened to Penzone make promises to Latinos, to immigrant rights groups and to undocumented youths like Máxima who wanted Arpaio out. He said he’d build trust and bring justice to the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office.

“It was still a little iffy ... is he going to be the answer that we need?” she says. “But he’s the best chance that we have for Arpaio to get out.”

She walked miles canvassing in the heat, registering new voters and campaigning against Arpaio.

On Election Night, she waited on the outcome with her community in Phoenix’s Grant Park. They’d hung a giant eviction notice symbolizing Arpaio’s time was up.

Standing in the grass, watching people praying, talking, playing with their kids, she remembered 2012 and how it hadn't mattered that they registered so many people to vote.

But when the results arrived, Arpaio had lost. Penzone won.

“After 24 years, Arpaio is going," she says.

Trump had won. "But it was this feeling, at least with this one race, people who have been dehumanized or criminalized by Arpaio could give a testament of how they were feeling," she says.

Máxima didn’t trust politicians, but she thought Penzone might listen to the people who helped elect him.

New sheriff, same policy

When Trump was elected it changed how Máxima viewed activism. More mothers and fathers were being deported. There was no middle ground, she says. Either you did everything in your power to keep families together or you were complicit in separating them.

In 2018, she took a job with Puente Human Rights Movement after working for other immigrant rights groups.

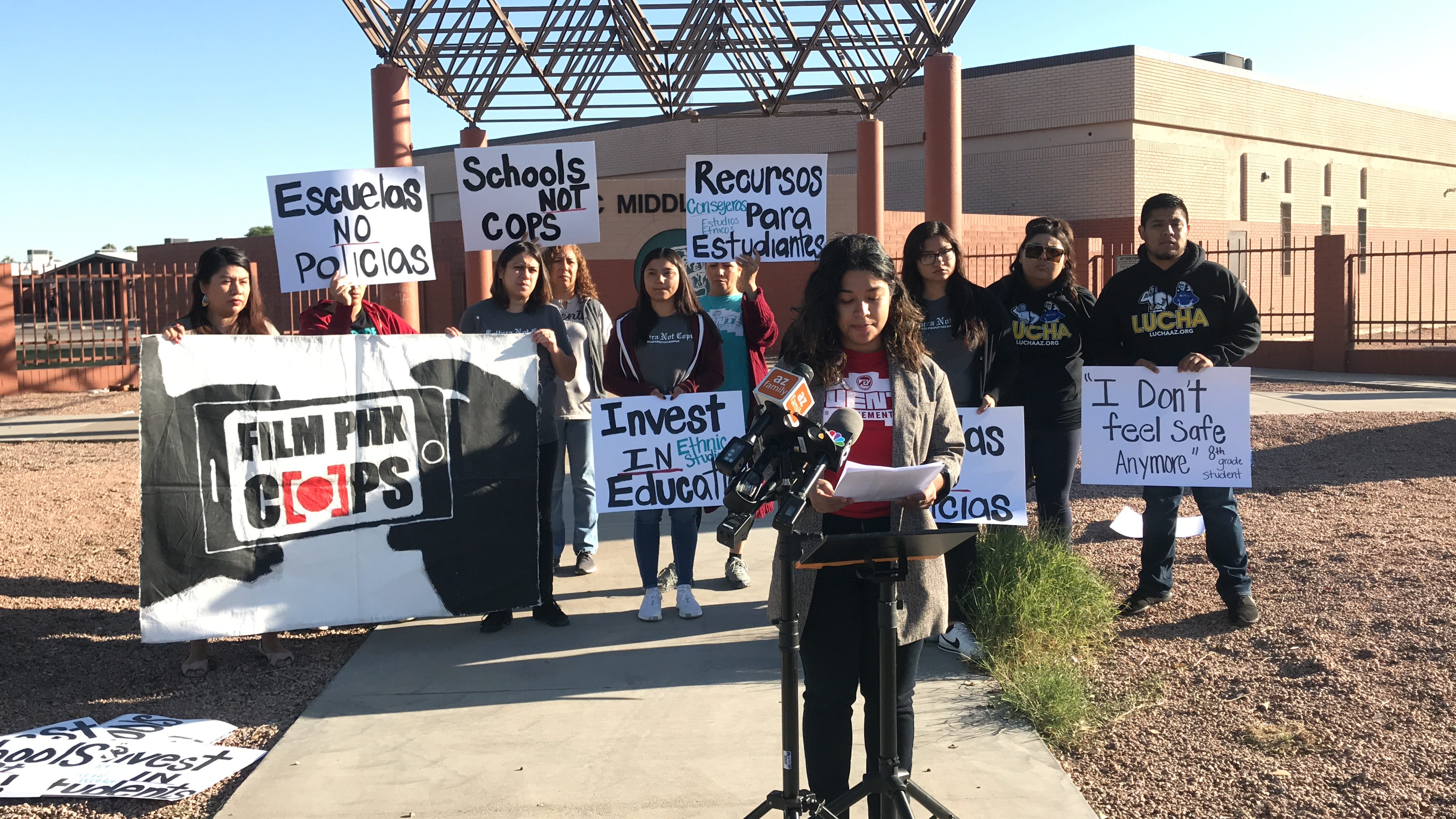

Puente wanted her to lead a youth campaign. They organized protests against police violence and to stop schools from using police as campus security, arguing people of color were disproportionately punished.

Máxima, now 28, encouraged an undocumented teen who didn't qualify for DACA to travel to the nation's capital to advocate for immigration reform.

“That brought me back to that trip I couldn’t make to D.C.,” she says. “To have her have that experience ... at the same time she’s advocating for her herself, her community, her peers, I wanted that for her.”

Máxima was also helping organize protests at Penzone’s Fourth Avenue Jail.

“We told Penzone to end Arpaio’s partnership with ICE,” she says. “At first, we thought he’d listen.”

He didn't.

A Puente organizer had been arrested by Arpaio's deputies for trying to block a roadway leading to a 2016 Trump campaign rally. She sued claiming deputies and ICE officials in the Fourth Avenue Jail had racially profiled her and were violating the constitutional rights of anyone held without probable cause for up to 48 hours after a judge ordered their release.

So-called "courtesy holds" or detainers kept inmates suspected of being in the country illegally jailed until they could be transferred to ICE. That often led to their being moved to a detention center where they awaited deportation proceedings.

In Penzone's second month in office, he announced that under threat of litigation, and after consulting with the Maricopa County Attorney's Office, his deputies would no longer offer courtesy holds for ICE. If ICE wasn’t there to pick up a person after a judge had ordered their release, they were free.

"So ICE will have to take a more aggressive position on how they’re going to act on those who are in violation of federal law as we continue to enforce state law," Penzone said at a 2017 news conference.

Penzone also barred ICE transfers from inside his jails.

But a backlash brewed when, about a week later, Penzone released at least 33 people who under Arpaio would have been held for ICE.

ICE argued for access to the jails to avoid the risk of people fleeing.

Penzone reversed himself and again allowed deputies to transfer people suspected of being in the country illegally to federal immigration officers.

Máxima had heard Penzone promise he would be better than Arpaio. But to her, it was more of the same.

She continued to help organize protests outside Penzone's jails, but there was quiet opposition to their activism from within the Democratic Party — "back the new sheriff or you'll get another Arpaio."

Everyone says Arpaio was worse. Máxima questions the difference when you're still explaining to a child that their parents were picked up by sheriff's deputies, transferred to a detention center and deported.

A distinction without a difference

The past three fiscal years, Maricopa County Fourth Avenue Jail ranked second nationally for ICE detainers or holds — requesting transfer of custody to immigration detention — totaling 9,448, according to data analyzed by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University. In 2016, when Arpaio was still in office, it ranked fifth for detainers and from fiscal years 2014 to 2106 detainers totaled 8,343.

Asked about criticism of allowing ICE in his jails, Penzone said in a statement to The Republic that his partnership with ICE isn't mandatory but ensures cooperation: “My position regarding consequences for violating the law is neither subjective nor influenced by politics. I will continue my commitment of consistent, constitutional application of the law while supporting other state and federal law enforcement agencies. I support immigration reform and DACA, and look forward to thoughtful legislation in support of a pathway to citizenship.”

When Penzone announced changes to Arpaio's partnership with ICE, he said "a formal written agreement is pending." In the three years since, immigrant advocates have repeatedly called on Penzone to release the agreement.

Norma Gutierrez-Deorta, a spokeswoman for the Sheriff's Office, told The Republic "there is not a formal written agreement" with ICE, nor does the law mandate "MCSO to have an agreement with ICE."

Rather, Penzone "provides ICE a safe space to do their job, just as he does with other law enforcement partners."

Penzone's spokeswoman said, "Immigration Customs Enforcement Agents interview every detainee at intake for the MCSO Jail system at the time of booking."

When the court notifies MCSO to process an inmate's release, federal immigration agents are notified that a detainee ICE flagged is being freed. That typically occurs about 5-7 hours prior to completing their release, according to a 2017 Penzone statement. MCSO again notifies ICE 15 minutes prior to the person's release.

"ICE has the opportunity to take custody of individuals they deem appropriate at the jail facility after the inmate is released from MCSO custody. ... If ICE does not take custody of them, they are free to leave," the spokeswoman said. "We do not accept nor facilitate ICE administrative detention requests, also known as 'courtesy holds.'"

Lena Graber, an expert on the role of local police in immigration enforcement with the Immigrant Legal Resource Center, said Penzone works more closely with ICE than most agencies she’s studied.

A lot of sheriffs “might let ICE in if ICE comes and asks to interview people, but they wouldn’t provide notice of release dates, they wouldn’t do courtesy calls to ‘Come pick this one up,’ especially not two courtesy calls per person,” she said. “They’re not just letting ICE have some access, they’re really facilitating it.”

She said booking is a complicated process so it’s uncommon for police agencies to allow federal officers to screen everyone they've arrested.

“Interviewing everyone at booking ... that is working very tightly with ICE,” she said. “That’s seeing your mission as the same as ICE. He’s definitely going above and beyond.”

Many law enforcement agencies have removed ICE from jails, Graber said, so it’s disingenuous for Penzone to argue it would be unfair not to allow ICE in his jails.

She pointed to Santa Clara County, California, which in 2011 limited its cooperation with ICE. “ICE is not allowed in the building for transfers and can’t interview anyone” without a valid arrest warrant or similar order signed by a judicial officer, she said.

Penzone is giving ICE a courtesy that he could end tomorrow if he wanted, said Melissa Keaney, a senior attorney with the International Refugee Assistance Project who specializes in law enforcement abuse of immigrants and refugees.

“It’s absolutely not true that local agencies are required to do anything vis-a-vis ICE,” she said. “They don’t have to provide an office for ICE.”

‘I hope I can breathe’

Máxima had been at the Phoenix protest for George Floyd so long that Saturday had turned to Sunday.

One last quick drive with a fellow legal observer to make sure protesters were safe, and she'd be home, sleeping in late and reading birthday messages.

They parked and saw police officers corralling protesters, making arrests. Police handcuffed Máxima and moved her with a group of young women to a police wagon. One of the women was pregnant.

They squatted in the wagon thirsty and sweating for about 30 minutes, she says. There was no air conditioning.

“I was just thinking, ‘I hope I can breathe,’” she says.

Finally, the wagon engine turned and they were moving.

Police took them to a Phoenix police precinct. In a cramped meeting room, the women compared notes. They all said they hadn't been doing anything wrong, just leaving the protest.

Máxima thought about the new coronavirus that had kept her home for weeks.

“There was no social distancing,” she says. “They did have access to a restroom but the restroom didn’t have soap. ”

They were at the precinct for about 10 hours as police processed the arrests of more than 100 protesters. Then they loaded a group in another police wagon and moved them to Fourth Avenue Jail.

When police moved her to a large hallway she stared at a long booth where the ICE officers worked next to jail officers.

"I was thinking, 'Why did these arrests start happening in the first place when people were leaving? This shouldn’t have happened and now I’m at Fourth Ave. and ICE is at Fourth Ave.,'” she says.

An ICE officer said her name. He asked for her Social Security number.

“They look me up and he says, ‘You have DACA, right?' He made this comment, ‘Oh, you DACA people, always going out there thinking you can protest and thinking you can do all these things,'” he says.

An ICE officer chided her for not applying for citizenship. “I said, ‘I don’t think that’s how it works,'” she says.

“He said, ‘You study immigration law? How do you know?’” They told her sit down.

“I’m relieved,” she says. “They didn’t tell me nothing about being on (ICE) hold.”

She was waiting to move to a cell when ICE called her again.

“I was just like, ‘No, so close,’” she says.

“He said, ‘I just got word that you actually are going to be on a hold, so that means that after you get released from jail from Fourth Avenue, ICE is going to be there to pick you up.”

She thought about being deported and everything she'd lose. Her family, her friends, a business she built with another Dreamer.

“I’m scared,” she says.

When deputies finally moved her to a cell, Máxima stayed silent, her thoughts festering and focusing on Penzone.

“I shouldn’t be here with ICE, worrying about being deported. And I wouldn’t be here with ICE if Penzone had listened,” she says.

Máxima got to make her first phone call at about 3 p.m. on Sunday. She called Puente.

They knew she’d been arrested and already had an attorney working on her case. They had organized a social media campaign calling on community and political leaders to flood Penzone, Chief Jeri Williams and Mayor Kate Gallego with calls for Máxima’s release.

“That was the first time I cried,” she says. “I was really feeling helpless ... I’m trusting you all to do what I usually am doing for others, to do whatever needs to happen outside to get me out.”

Hours more passed until officers called Máxima for her 8 p.m. initial appearance before a judge. She walked into a courtroom with several of the young women who'd been with her in the cell.

It was the first time she spoke with her attorney. Immigrant and civil rights lawyer Ray Ybarra Maldonado told Máxima they were all fighting for her. But it’s bad, he said. They were recommending charging her and dozens of others arrested at the protest with a Class 5 felony for rioting.

“Felony.” Máxima struggled to hear anything beyond that. A felony meant no DACA. They could send her to a detention center and deport her.

“They could take away everything,” she says.

Her attorney told the judge about her ICE hold. She heard a gasp from the women sitting behind her, who’d looked to Máxima for help with who to call and how to exercise their rights.

They didn’t know Máxima wasn’t a citizen. She was escorted back to the jail cell, where the women told her they were sorry that they were going home and she wasn't.

At first, Máxima didn't understand why everyone who had arrived with her was being released and she was still locked up. Even people who arrived hours after her were being released.

Máxima suspected Penzone's deputies had placed her on courtesy hold, keeping her past her court-ordered release, for ICE, just like Arpaio's deputies had in the past.

Máxima says deputies finally called her name at about 2 a.m. An ICE officer shackled her wrists and ankles. They moved her to a van with two young men MCSO was also transferring to ICE.

When Máxima was released it was with two other noncitizens who had been arrested in the protests. It wasn't a coincidence, she thought. MCSO had held them all so ICE could conveniently pick them up at exactly the same time.

Gutierrez-Deorta, the MCSO spokeswoman, said, "There are a myriad of factors that can contribute to inmates being released at different times. Releases are processed promptly in the order they are received from the courts."

'I’d never see him grown up'

At ICE's field office in downtown Phoenix, Máxima tried to call her attorney.

His wife picked up the phone. She told her a crowd was protesting outside the ICE office and dozens of community leaders had sent letters calling for her release.

But her attorney, Ybarra Maldonado, warned Máxima that ICE soon planned to move her to a detention center to await deportation hearings. He wasn't giving up, and he didn't want her to, but she needed to know what would happen next.

An ICE officer told Máxima they'd send her to the Eloy Detention Center. Another officer remarked that Máxima had been arrested with protesters “out there just starting some s--t.”

Asked about remarks that Máxima claims ICE officers directed at her, an agency spokeswoman provided information to file complaints and said: "As public servants working for a law enforcement agency, ICE employees are held to the highest standard of professional and ethical conduct. Allegations of misconduct are treated with the utmost seriousness and investigated thoroughly. When substantiated, appropriate action is taken."

Weeks earlier, Máxima had helped organize a massive protest outside the Eloy facility, one of the nation’s largest jails for undocumented immigrants. Protesters social-distancing in their cars, called on ICE to release migrants before they contracted COVID-19.

Máxima worried she might become another forgotten migrant in Eloy with the virus.

She asked to use the phone and called her mom.

“You’re strong, you know what to do … and we’re all here for you," she remembers her saying.

Laying on a concrete bench in a holding cell, Máxima thought about who she'd leave behind. “I thought about my nephew and how I’d never see him grown up,” she says.

She’d be deported, moved to the other side of the wall, the other side of a border to a country she didn’t remember except for the sound of rocks and gravel under her feet when she was 5.

She wept thinking that her nephew would forget her. Would she hold him through a border fence?

Máxima can’t remember how much time passed before an ICE officer called her name.

“He said, ‘You’re being released,” she says.

They put an ankle monitor on her. As she walked outside Máxima could hear chanting.

She turned a corner. She could see her best friend and her mom. Someone wrapped their arms around her. They cheered and asked her to say something.

“I just said, ‘Thank you,’” she says.

They were too late for one young man, a noncitizen arrested in the protest who had been moved to a detention center. Another man's mom and girlfriend were there to plead for his release.

Máxima went home, showered, slept. She'd forgotten about her birthday.

“I needed to be alone,” she says. That same day, Máxima started making calls, organizing to stop her deportation.

'We’re starting to elect our own people'

Máxima’s attorney, Ybarra Maldonado, said the judge rebuked Phoenix police, saying officers did not have probable cause for most of the felony arrests they made the night of the protest.

Máxima's arrest is a prime example of why immigration officials shouldn’t be inside local jails, transferring them to detention centers before they’ve had a trial or due process, Ybarra Maldonado said.

“We have an amazing young woman who has accomplished so much in her life and who was falsely arrested,” he said. “If it wasn’t for a tremendous amount of community support … she would be sitting in a COVID-filled detention center.

"Cases like this, they happen every single day in jurisdictions where ICE is in local jails, you just don’t hear about them."

The total number of people with confirmed COVID-19 cases is 689 as of Sept. 1, according to ICE data for Arizona’s four major immigration detention centers. Some detainees may no longer be in ICE custody or may have since tested negative for the virus.

It's time for Penzone to own his policies and their impact on people like her, Máxima says.

“He could’ve stopped this,” she says. "He says he supports Latinos and he supports immigrants — he’s lying.”

Days before Máxima’s June criminal hearing, her attorney learned the county attorney wouldn’t prosecute her and the case was referred to Phoenix prosecutors. But because of her arrest and because ICE officers had placed an immigration hold on her, she still faced deportation.

State and local politicians wrote letters and advocated for the "Dreamer" who'd done everything right. It made Máxima sick thinking other migrants wouldn't get the same support.

Máxima's attorney said Phoenix police had mistakenly recommended Class 5 felony rioting charges for her and other noncitizens arrested at the protest when they should have been charged with only a Class 1 misdemeanor for unlawful assembly. Máxima went to county and city courts to get paperwork to show ICE there were no criminal charges against her.

In late June, Ybarra Maldonado called to tell her ICE officials had terminated her case. But she still had to return to the ICE field office.

Outside, she took deep breaths, remembering being one step away from detention and one step closer to deportation. Inside, an ICE officer handed Máxima her driver's license, saying they'd kept it by accident. She handed them her paperwork. They told her to sit, and cut off her ankle monitor.

Máxima was free, for now.

Ybarra Maldonado said that while handling Máxima’s case, he'd received an email from Penzone’s reelection campaign.

“I remember the celebration of Arpaio being defeated,” he said. “Here we are years later, but we still have ICE in the jail. We definitely feel the mistrust with Penzone, with the Democratic Party."

"At least with Arpaio, we knew where we stood and we knew we had a good chance of beating him in court. We sued Arpaio and we'll sue Penzone if he remains focused on doing harm to our community," he said.

Penzone faces Arpaio's former Sheriff's Deputy Chief Jerry Sheridan in the November general election.

“He’s going to want the Democratic votes and the Latino votes,” Máxima says. “It’s been four years ... and you have failed to be bold enough to get ICE out of the jail. At this point, it’s not enough to be the other candidate — to be the Democrat. We’re starting to elect our own people.”

Máxima knows there are still those who think anyone is better than Arpaio. She’s sick of settling.

She knows it won’t be long before she’s helping to organize protests outside Penzone's Fourth Avenue Jail for another mother or father picked up by ICE agents inside the jail.

After her release, Máxima visited her nephew. Not through a border wall, not after her deportation, not pushing her hands through a fence separating sister cities.

Máxima wrapped him in her arms. She held him close.